Breadcrumb #29

DAN POORMAN

Because I've casually used the term "eclipse," I have to elaborate. So I begin with tremendous frustration, "The syzygy is this: I am the sun and he is the moon and she is the earth — and we're all just fucking standing in the middle of Ferber, and it's 11 at night, and...my life is over, Priya."

I may confide in Priya with abandon, but at the end of the day I always decide that I dislike her, that she's a quack even if she doesn't have her doctorate yet, that she's nowhere near even the lawn seats overlooking the Scoville spectrum — and so death to that particular sample of Rate My Professors users with poor taste who, whether or not the woman has actually seen and reveled in it, still have given her the benefit of that omnipotent chili pepper.

But I'm sure she hates me too.

"So you consider this a religious experience," she says. She sits with perfect posture, and I know she is unbiased, that every cover letter she's ever written highlights her professionalism — but I can also smell her disapproval.

I tell her something true: "I hate having to explain this." She apologizes, her eyes on the ground.

I am talking to Priya about this moment, and she is the dart board to my fistful of darts, in that every now and then a part of the story will strike her in the right spot, inches closer to the bull's-eye, while the rest of the words I am saying miss completely, flying flaccidly into the wall or onto the floor. I pause to tell her this.

"Yes. But what more about Ferber?" she redirects me.

What's more about Ferber: I live on the second floor of Ferber East. My roommate, George, flunked the fall, so it's spring when I'm left to this converted single. George's mattress is my closet, George's dresser is my bookshelf. George's father's winter jacket, left here mid-move, sometimes is my winter jacket. It hangs alone on a hook George often used.

On the night in question, Jane is there. "She is perfect," I tell Priya, for context. Nobody is, but OK, she says with one look. Her adjunction is showing.

But Jane is petite, at 5'6", with hair that is wavy and apt to tangle for sensual purposes, fair skin but I'm not racist, round eyes you might call hazel in an eighth-grade poem. Jane has that name that makes me think of Tarzan. She wears, with modesty, a nude B-cup bra and a tie-dye shirt. But Jane's not a Deadhead. In fact, she's never smoked a thing in her life, and she's wearing sweatpants branded by the name of her high school and also: boys socks.

"Priya, Jane made popcorn in my microwave."

We met in philosophy class. From Hegel to Nietzsche. Sometimes she puts glasses on. She's from Buffalo.

“We met in philosophy class. From Hegel to Nietzsche. Sometimes she puts glasses on. She’s from Buffalo.”

The film is Batman Returns, and the last time she saw it she was 14, and she loved it, or so she tells me — and she likes that I have it on VHS, and that I tape black towels over the windows to muffle the light and as much of the noise from the quad that I can. We have movie nights that we're calling platonic, and yes, we are best friends, and she tells me first semester was lonely, and her roommate is a simple bitch, and she points to my beanbag and chuckles, "Cool beanbag," and she puts a Tropicana in my fridge, and I tell her Danny DeVito gives a truly remarkable performance, and does she remember when he bites that guy's nose?

I think I'd like Priya better if she asked me more questions like "Would you call it cuddling?" I am ready to answer that. I'd say, "I would."

The rotten astronomy takes place in an evilly brief plot of time I'd compare to a caterpillar's prick: slight yet undoubtedly scarring. I'd excused myself to the bathroom, four doors down my hall. Told Jane, "Pause it on the title card" because that just makes sense to me.

"I remember she giggled," I'm saying to Priya. "She giggled and said, 'All right, I'll be waiting,' as if maybe we'd bang, as if maybe I'd come back and she'd be in some negligee." Priya asks if this is about sex. I swear to her it's not. She urges me onward. She's watching the clock.

If I am the sun, I am risen from the restroom, having blotted nervously at my hair with faucet water, having only pissed a little — an amount you might legally call a tinkle. "I am the portrait of innocence" is something I actually tell Priya. She never writes this down.

The moon is the Terror of Ferber East, the guy I've dubbed "Agent Yacht" to a few of Jane's giggles past, the star of the security blotter in his naked splendor (his salmon shorts are crumpled in the doorway of his room). His ass is pasty, and on his back are scars from a lacrosse stick or two. Careful pimples on his shoulders. Sweat that'll taste like Rolling Rock if you try it. He is fit and stinks of reefer, and he is wielding his ruins of the day: a detached railing, likely from third-floor Ferber West, splintered and repurposed.

And then there is my earth, on the other side of the moon, and she's captivated, frozen. Her grip loosens on her Tropicana. There are a few stray kernels of popcorn at her feet. The moon breathes heavily. I have reason to believe she is trying to synchronize her own respiration pattern with his.

"Because it wrecked my life, it seemed like it lasted forever," I tell Priya. A few things I could add but don't: Space is infinite; terribleness is infinite; I thought of putting a knife in Agent Yacht's spleen.

"So then what happened?" Priya asks, and she's picking up her books.

"It ended fast in real time," I admit. What happened was: I made some kind of gurgle, and Yacht turned quickly to the sound, his member flopping with him — and he got real red, and he screamed into the void of second-floor Ferber East, "ALPHA — TAO — OMEGA!" before retreating to his smoky dorm.

And then Jane told me there'd been a loud crash, and she'd crept from my room to explore it, and "You know, I'm really tired, can we do this some other time?"

"Priya, she hurried together her things and left me alone with my TV" — as it projected Burton's title card, sad and still, save for a few traces of static that passed like hiccups, or EKG spikes.

Now Priya — this fake teacher, this ice queen — asks me passionlessly for an epilogue: "Where is Jane now?"

I recount just last week, on a walk to Burrito Junction, cutting down College Ave., and I see her outside a big house tattooed with spray paint letters, and she sees me, and I stop like I sometimes feel the earth does truly, and she's in some tight dress, and she's got some defunct Tropicana just sloshing around in a Nalgene, and I ask her, "What's up?" and she says, "Nothing, you?" and I say, "Where you going?" and Priya—

"She said, in the middle of a crowd, 'Out,' and walked directly inside."

Breadcrumb #28

BOB RAYMONDA

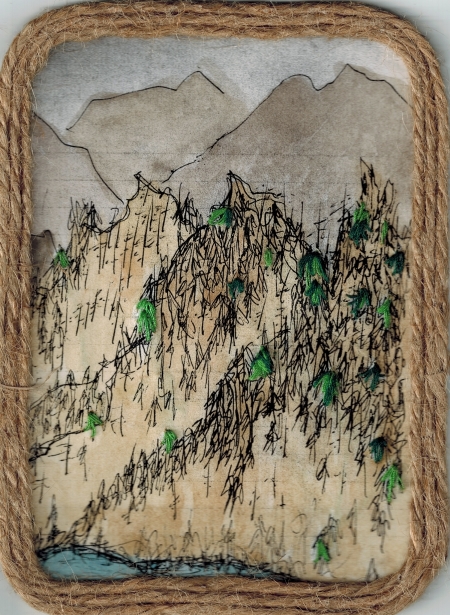

Pavlima sits hunched over a dimly lit desk and revels in her work. She’s surrounded by giant spools of fabric throughout her small workspace. Each spool a different color representing another facet of the organization that contracted her. Adjacent to her desk is a wireframe dressing dummy that she adjusts after measuring her clientele, rusty from decades of use. Wrapped around it are thick swaths of formless yellow fabric. Eventually these will transform into custom-fitted cloaks for the paramilitary security agency that governs the upper district, but not yet, for she is only getting started.

She agonizes over one of the patches that will emblazon its breast and shoulders — a lone wolf standing underneath a starry sky, looking upon a thin crescent moon. A growing pile of the small triangles sit rejected at her boot. To the untrained eye, they each look like perfect replicas of one another, but there is one misplaced stitch in each. Pav is what you’d call a type-A personality, so if her work isn’t exact, she doesn’t use it. This is both the reason her employers hired her, and the reason she drives them crazy. Every single piece is made subtly unique while remaining uniform and is almost impossible to replicate with a sewing machine. So while they keep indoctrinating the youth into their cause, she can’t keep up with their demand, and some of the market streets remain unpatrolled, much to the Wolfpac’s chagrin.

Pav’s fingers are nimble, but they aren’t quick as she loops her needle in and out of the patch with spidersilk thread. Traditional industrial folk music plays out of the speakers mounted in the corners of the room, which is the easiest thing for her to stitch to. It used to play at a deafening volume, but her neighbors have been reporting her to the Wolfpac for noise violations, so she’s toned it down a bit. A stale coffee sits close to her left hand, and she continually reheats the coffee to sip throughout the day. Most visitors scoff at her working conditions, but she wouldn’t have it any other way.

Something buzzes loudly and she connects two of the stars together with a single stitch. She could tear it out, or hope that no one would notice, but she throws it at the ground in frustration and grabs the communication device from her hip.

“What?” she seethes, curt.

“Kendall is on her way for her uniform fitting,” responds a gruff voice on the other end. Root, her employer. She imagines herself sewing the poisonous thread she uses through his navy blue tentacles, and it relaxes her for a moment.

“She imagines herself sewing the poisonous thread she uses through his navy blue tentacles, and it relaxes her for a moment.”

Pavlima lets out a snarled laugh. “Are you kidding me? I told you she could come next week.”

“There was an incident.” His breath on the other line is heavy, ragged, as if he were wounded. She’s glad. “We need to have 23 new recruits robed up in the next six weeks; we can’t allow you to dawdle, Pav.”

“That’s impossible, Root.”

The signal goes dead, and there’s a knock at the door. She throws her communication device against the wall and it shatters, which pleases her. She answers the incessant pounding and is taken aback by what she sees. For some reason she’d pictured Kendall as a man, but the recruit was anything but. All high cheekbones and rouged lips, accentuated by a tattoo local to one of the under dwelling communities where Pav grew up. Pav lets the fresh-faced girl enter before slamming the door shut behind her.

The recruit takes one look at the monstrosity on the dummy and the stack of patches on the floor and says, “I thought my captain told me to be here now. Should I come back another time?”

Pav chuckles as she sizes the poor thing up — young and fresh faced like Pav was when the Wolfpac snatched her up from her mother’s free clinic in the Eastern Summit. “No, he certainly told you to be here now, so we’ll do our best.”

The recruit nods, “Where should I stand?”

“Where you are is fine, please disrobe.”

The girl’s eyebrows raise, but she obliges. Her body is covered in pockmarks and scars, her wrists burned by the telltale sign of plasma cuffs. Pav has no idea how she’s raised herself this far up the ranks, but she’s intrigued. She rips the misshapen fabric from the dummy and drapes it over the girl's shoulders, but not before studying her nakedness. She grabs a pincushion from her desk and starts pinning the fabric where she’ll need to make adjustments so that it is both form fitting and breathable.

“So what’d they tell you, Kendall?” Pav says to the girl, a pin clenched between her teeth.

“Sir?”

“To get you to abandon your family.” Kendall’s shoulders tense up, and Pav smiles, pushing one of her tentacles out of her face.

“Sir, I just came here to get fitted, not talk politics.”

“Oh, I’m not judging you,” the girl yelps as Pav accidentally pricks her with a pin, “Sorry about that. But, I’m not judging you. I certainly didn’t grow up ever seeing the sun.”

Kendall relaxes, but not entirely. “That if I could make a difference in my own life, I could elevate my little brother. Let him live in my apartment.”

Pavlima nods and takes a look at the work she has cut out for herself. Kendall is stunning in the unfinished uniform, and Pav wants to make sure she’ll always look that way. She wants to have a hand in that. “So when will you let me buy you a drink?”

Pav takes notes in her chicken-scratch handwriting marking where she’ll have to alter, and unpins the girl from it. As it falls in a pile at Kendall’s feet, she covers herself and smiles at the seamstress.

“I didn’t need to get undressed.”

“Nope.”

Breadcrumb #27

MADELEINE HARRINGTON

The delivery men propped me against the wall. You left me there for hours, and I looked out your very small window and pretended to be artwork. You paced the room and sized me up. Finally, you took me off the wall and climbed on top of me. You were nervous and stretched your limbs with well-practiced hesitancy. You’re afraid of settling I’ve learned; you like the idea of it but there’s something that keeps you from fully giving in to gravity. You change positions frequently, every seven and a half minutes in fact, even in your deepest sleeps, so that your silhouette never has time for significant indentations. That night, you lay on top of me and we examined the cracks and rivers in the ceiling. While I hardly fit in that room and you covered me with a shiny red sleeping bag, those were my favorite days with you. It was just the two of us, staying up late, bracing for the infinite, daunting future.

You never gave me a frame, so there was always a strange, sinking dance between you and your guests. Kissing while descending is difficult, I’ve realized. It requires a silent synchronicity, a certain level of trust; otherwise it just looks wrong, like two people drowning.

The first guest was too tall for me. His feet dangled over my edge, and in his sleep he struggled to tuck them into the sheets. Your bodies didn’t always align, but you put in the effort. He smelled sometimes and made you angry, but he changed the lightbulbs and stayed around for a while. And the cadence of your voices together felt low and comfortable, like the tune to the theme song of a television show that you used to love.

You painted your walls sea green and it spilled all over me. You worked well into the night and fell asleep on the couch, leaving me alone with my stains to settle. The second and third guests alternated into the summer. When they tried to hold you, you complained about the heat. When your ex-boyfriend visited, you fucked aggressively and woke up periodically. The sheets came off my edges, the red sleeping bag kicked to the corner. When he left, you entered me like I was a warm bath, put the sheets over your head, and lay so still that I started to worry. Eventually, though, I began to hear the unmistakable vibrations of weeping. You cried always with your face smothered by pillows, your body like a crescent moon.

“You cried always with your face smothered by pillows, your body like a crescent moon.”

You welcomed the fourth and fifth guests with ambivalent embraces. I stopped counting the amount of times you went to the bathroom throughout the night. You kept things inside of me — a hairbrush, a book, Altoids, a museum brochure — that were better suited for your shelves. It was because you were lazy partially, but I could tell that you liked it — having all your possessions within reach, floating amongst you on your island.

The sixth and seventh guests didn’t even spend the night. I woke up once at 4 a.m. to see a mouse watching us. I will never understand why humans fear these animals so much, but I’ve also learned that nearly all your emotions are disproportional. You hung artwork, posters, newspaper clippings that arrived and vanished with their relevance and your boredom. The mouse lived with us for weeks and you slept through all of its appearances. You had a boyfriend. You bought a comforter, wrapped me into it with meticulous affection, and stuffed the red sleeping bag deep into the closet. When the mouse was finally gone, I felt guilty, like I had a secret from you. You had a breakup and hid inside of me. You drooled and flinched from nightmares. You found another boyfriend and together you painted the walls back to white, and the smell and general chaos of the room kept all of us up late.

We moved: more natural light, a larger room, an optimistic outlook. You had another breakup and repositioned me to face the door. We fell asleep to the cadence of your weeping and woke up early from fitful, incomplete sleeps. You never got around to buying curtains and, on good days, the light touched every object you owned with firm persistence.

One morning, you woke up and something felt different. Your limbs felt heavier, your breathing rhythmic and void of restlessness, and I could tell you were realizing just how alone you really were. And as the sunlight crawled across the floorboards and sloped along every surface, I felt a sense of sheepish excitement; it was just the two of us again, examining a crack in the wall, bracing for the day.