Breadcrumb #33

DANIELLE VILLANO

I hear her whispering to dead people, sometimes.

“Formaldehyde, glutaraldehyde, methanol, ethanol, phenol, and water. That’s all it is. There’s nothing to worry about, when you think of it that way.”

We are working late one night and I finally raise my voice enough to say: “You are very good at what you do.”

She hears me but doesn’t respond for a moment, focusing on blending the complexion hi-lite onto Mrs. Simpson’s cheekbones.

“That’s a lot, coming from The Artist,” she says, using the nickname on my apron, the gag gift from last year’s company Christmas party.

We smile at each other over tubs of chemicals and stainless steel surgical supplies, and my head feels light, and we make the unspoken decision to go home together.

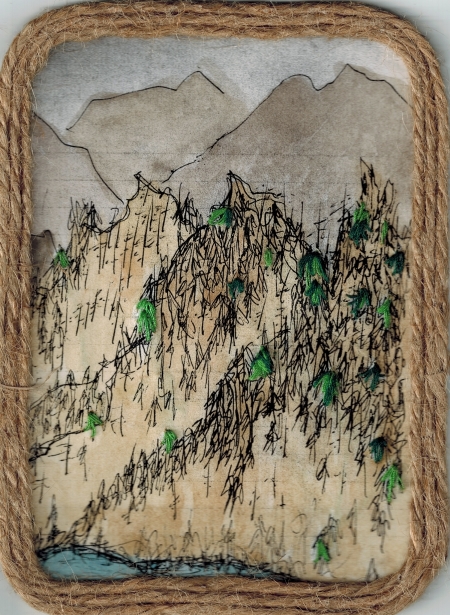

I’d never really noticed how close I lived to work until I walk home with her. It is quiet aside from the ice crunching under our feet as we take the 10-minute walk past chiropractor offices and Chinese food restaurants so warm that the steam from the open door makes clouds in the cold air. The sky is awash with dark colors, like liquid swirling down the drain. When we get to my complex I feel embarrassed by the broken front gate, but she kisses me up against it anyway. Her mouth is slippery, soft. Her pulse jumps in her throat. We stumble into my apartment, shaking snow off our boots. We are surrounded by deadness all day, and now all I can feel is this: the pressure of her hand on my lower back is a hot iron.

“So this is where The Artist lives,” she says, and flicks on the light switch. And then she sort of yelps, because my mother is sitting, like some sorry old mannequin, at my kitchen table.

“I couldn’t stay home,” my mother says, looking past The Girl and me, to a point above our heads. “I saw your father again.”

My father died three years ago, and every few weeks my mother calls crying because she saw my inconsiderate father finish off the carton of milk and leave it empty, out on the counter. How she got across town to my building at this time of night I have no idea, as her knowledge of the bus system is very limited, and a quick scan of the room comes up empty for a sight of her purse. My mother is small and shriveled and I suddenly feel embarrassed for her eyes, which are sunk so comically low in their sockets. The Girl is looking at me and whispering, Should I go, should I go, and then my mother finally recognizes her presence and says, “Oh, you brought a girl home.” And then she breaks down and cries in a way that reminds me of a little bird left out to freeze.

“And then she breaks down and cries in a way that reminds me of a little bird left out to freeze.”

“I’m Brianna,” The Girl says in the voice she reserves for dead people. She walks over to the table and sits down at the chair across from my mother. I want to say: No, don’t. We do not need to know each other like this.

“I work with your son at The Home.”

I can see my mother taking in the details of The Girl sitting across from her. Dyed dark hair, sloppily cut. Kohl-rimmed eyes. The silver ring in her lip that, some nights, when I lie awake in bed, I imagine grazing with my teeth.

“Such a nice girl? Working there?” My mother looks between the two of us.

“I can still make dinner,” The Girl — Brianna — says.

I lead my mother over to the couch and Brianna rummages through the cabinets until she finds a can of ravioli. She locates the can opener and gets to work. The plop of cold pasta into the bottom of the pot makes the bile rise in my throat, and I am struck dumb by the fact that I can tear people open and suture them closed day after day and I cannot tolerate the most mundane of noises.

My mother says, “It’s so dark.”

I tuck a blanket up underneath her quivering chin, and when she shuts her eyes the resemblance to Mrs. Simpson from earlier is so strong that I have to lean in close to make sure she is still breathing.

It is after midnight when I settle into a chair and spoon lukewarm pasta into my mouth. Brianna licks sauce off of her lip ring. The moon is a shining steel basin outside the window.

I want to say: I often catch myself wondering when my mother will find her way to the embalming table.

Brianna speaks first. "At this time of night I feel most alive. Don't you?"